Lev Sergeyevich Termen [Léon Theremin] was born in St Petersburg in 1896, and from an early age it was apparent that he had a natural gift for a variety of disciplines, from astronomy and physics to music. As a student at what was by then Petrograd Uniersity, he began to conduct experiments with high-frequency currents, magnetic fields and oscillators; though interrupted by the First World War, his research continued at the city's Physico-Technical Institute, where he eventually assembled an instrument, initially called the 'etherphone', which came to the attention of the very highest authorities in the fledgling Soviet state. Lenin himself became an enthusiastic advocate of the instrument, after it was demonstrated to him personally by Theremin in 1922; the head of the USSR, who famously stated that "Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country", saw potential in linking this radical electrical invention to the wider revolutionary project. The inventor was accordingly dispatched on tour to advertise his innovation to the masses, enjoying free passage on the railways (themselves an emblem of the Soviet Union's growing technological power). On his return, he was able to capitalise on his prestige with further experiments, including producing the country's first fully-functioning television apparatus. In 1927, "a foreign extension of his agitprop barnstorming" was agreed, this time throughout Western Europe, and Theremin travelled to Berlin with a quartet of musicians from the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra - and the blessing of the Soviet Intelligence Services.

|

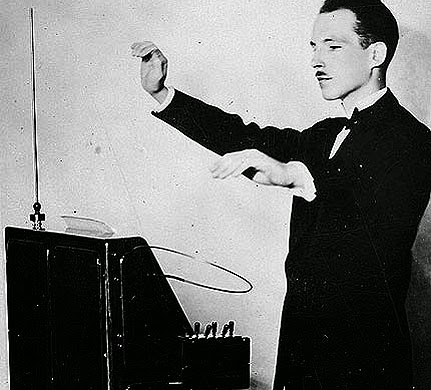

| Theremin performing on the Theremin, c. 1928 |

Enthusiastically received in Germany and France, where many etherphone recitals were sold out, by the time he reached London Theremin and his 'magic' device were something of a sensation. He gave demonstrations at the Albert Hall and performed before Arnold Bennett and George Bernard Shaw, before finally sailing for New York at the very end of 1927. Along the way, the instrument’s name became interchangeable with that of its creator. The further he travelled, the further its status altered, from its Soviet origins as the ultimate democratic musical object, to a novelty ('no expertise necessary!', as its early American promoters boasted), and then an exclusive plaything of the rich. Theremin gave concerts with virtuoso Clara Rockmore at Carnegie Hall, and even after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 still harboured visions of achieving mass appeal – an RCA advertisement suggested ‘a Theremin in every home’, a bold ambition which sadly never came to fruition – the instrument’s main appeal was for electronics hobbyists. The most notable of these was Hugo Gernsback, an entrepreneur-publisher of popular science magazines such as Modern Electrics. Credited with the creation of the term ‘science fiction’ and popularising it through his ground-breaking genre magazines (beginning with the hugely influential Amazing Stories), Gernsback himself dabbled in inventing electronic instruments, including the ‘Pianorad’. Continuing Theremin’s lineage, Robert Moog, creator of the first modular synthesizer which bore his name, the Theremin of its day, purchased the ‘build-it-yourself’ instructions from one of Gernsback’s publications.

|

| Poster advertising the first Theremin demonstration in the USA; New York, 1928 |

Though in his New York heyday, Theremin continued to entertain visiting dignitaries and enjoyed the patronage of various high society benefactors, the commercial success he had anticipated showed little sign of materialising, despite his diversifying into alarm systems and other electronic innovations. The Theremin had been adopted in the early 1920s by Soviet film composers, amongst them Shostakovich, (and in 1934 made an appropriate appearance in the score for the propaganda film Komsomol – The Patron of Electrification), and Hollywood was not long in embracing the instrument, reviving its popular fortunes. Connoting strangeness in every sense, its ethereal sounds soon became synonymous with not only disturbed states of mind – pioneeringly used by Alfred Hitchcock in Spellbound (1945) – but also other worlds; as such, it was ideal to be applied to science fiction film soundtracks: Rocketship X-M (1950), The Thing (From Another World) and The Day the Earth Stood Still (both 1951) are among the earliest examples. The subsequent ubiquity of the Theremin in the genre meant that by the time of Tim Burton's 1996 sci-fi homage, Mars Attacks, its inclusion by composer Danny Elfman was regarded as playful parody.

Footage of Theremin in later years, accompanied by his daughter Natalia

Whilst the instrument that bore his name became ever more established in the popular culture of the West, the events of his own life, shrouded in mystery and containing fantastic elements, have been exhaustively recorded by biographer Albert Glinsky in Theremin: Ether Music and Espionage and re-imagined in the 2014 prize-winning novel Us Conductors by Sean Michaels. After his return to the Soviet Union on the eve of the Second World War (whether voluntarily or not is still the subject of speculation, as the ever-vigilant Soviet Intelligence Services are likely to have kept a close eye on him throughout his Western adventures), Theremin’s technical genius was applied to the service of the state during the Cold War – namely, inventing devices for intercepting ‘enemy’ communications and spying – and he worked in seclusion over the following decades. On the fall of the Soviet Union, he re-emerged in the West, even making a triumphant return to New York in his dotage, an improbable event captured for posterity in a documentary released in 1993, the year of his death, Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey; an apt title for a man whose lifetime spanned two centuries, both World Wars and the entire Soviet era, and whose musical and scientific legacy remains relevant today.