Guest post by Peter Martin, see also Old Rope blog:

https://oldrope.wordpress.com/2020/02/06/saga/

A comic about an alien family on the lamb in a flying tree in space? You had me at comic, but yes,

obviously I want to read that. It’s been going since 2012? Why has no one told me about this sooner? My dear friend Giro recommended me the curious tale of the Saga, er, saga. Yeah, it’s not a great name I grant you, but to quote Lisa Simpson, it’s apt – APT! At the time of writing, the 54 issues of the series have been collected into nine volumes, with six comics comprising each story arc. The series is planned to finish at 108 issues or 18 volumes. I have read four so far and it is these that inform the below.

Drawn by Fiona Staples and written by Brian K Vaughn, Saga follows the plights of Alana and Marko, a couple who are on the run from both sides of an intergalactic war. Their crime is falling in love with the enemy and having an interracial baby, a political affront to the two extraterrestrial species embroiled in the long-standing conflict. They hop from planet to planet, hunted by soldiers, hired assassins, irate parents and disgruntled exes, all the while just trying to live a normal family life.

Saga is no ordinary comic and not just because it is narrated by a baby. Though it would be disingenuous to say that the medium is all unsubtle macho superhero fodder – and also conceding that I am no expert – it’s rare to get something so rich and varied in the mainstream (it’s published by Image, one of the big three publishing houses). Saga’s themes of family, motherhood, racism, war, politics and sex, while by no means unique to this book, are a rich and refreshing blend. Not only are the heroes young struggling parents, they are actively refusing to fight in the war that rages around them, setting this story apart from much of the work we might wish to compare it to. Pacifism is seldom at the forefront of popular sci-fi, bristling with blasters, troopers, space-battles and laser-swords, nor its fantasy counterparts with whopping big blades, magic and monsters. That’s not to say that Saga doesn’t have its fair share of any of the above – it does in spades – and barely an issue goes by without some form of gratuitous, albeit funny, violence.

Our protagonists are basically sexy alt-rock tattoos come to life. Alana, with her dyed fringe and unlikely post-natal smoking bod, is from the planet Landfall where the locals sport delicate insect-like wings. Her beau is Marko, all brooding brows, trench coats and a massive pair of curly goat horns. Phwoar! Don’t worry, they regularly go at it like hammer and tongs, as if unable to resist the collective yearning of hundreds of thousands of swooning readers. Sex is never shied away from throughout the pages of Saga, be it the impossibly hot and passionate form in the early days of Alana and Marko’s relationship, the lovesick longing of the hit man loner reminiscing of his time getting it on with an armless spiderwoman (armless not harmless, she too is a deadly hired assassin) or the seedy underbelly of alien sex work where anything goes. Taboo is a strong undercurrent, from forbidden love in the prism of societal racism lived by our heroes or the homophobia experienced by journalists Upsher and Doff, to alien fetishism, subversive literature and indeed the belief in peace in a time of war.

Taboo also bleeds into real life with several instances of censorship affecting the book. As a young mother, Alana is regularly shown breast-feeding Hazel – tolerable until it graced the cover of the hardback edition prompting squeamishness from retailers. Digital editions of the book were also briefly censored for an act of homosexual fellatio, shown on a blurred TV screen. The American Library Association included Saga in its 2014 list of the ten most frequently challenged books that year, for containing nudity, offensive language and for being “anti-family, … sexually explicit, and unsuited for age group.” And people wonder why it sold so well.

Like many endearing works of serialised fiction, one of Saga’s strengths is its cast of thousands. Alana and Marko may be recognisable lead characters – fit, loveable, morally right – but they are ably supported by a bonkers, imaginative and genuinely diverse bunch: Izabel the disembodied severed-at-the-waist war casualty teen baby-sitter, a sort of floating ghost with hanging entrails; Prince Robot IV, from a breed of royal androids with TVs for heads; the Freelancers, with their distinctive definite articles, The Will, The Stalk, The Brand; Marko’s relatably in-the-way mum and dad, but doting grandparents to Hazel; Lying Cat – a giant feline who speaks only to tell if someone is fibbing or not; whatever the heck loveable fan-favourite Ghüs is; and of course D. Oswald Heist, author of the dangerous polemic that ‘radicalised’ Alana and Marko.

A Night Time Smoke, the fictional novel by Heist, is shown in glimpses through the perspectives of characters on all sides of the war. From what we know of it, at face value it’s a fairly trashy affair, akin to pulp fiction or throwaway romance of the Mills and Boon ilk. Coursing through its pages, however, is the outrageous message that war is – get this – ‘bad’ and worse, the cover art shows us that the principal characters, Contessa and Eames the rock monster are from different races.

I’ll admit it, I’m a sucker for a text within a text. From

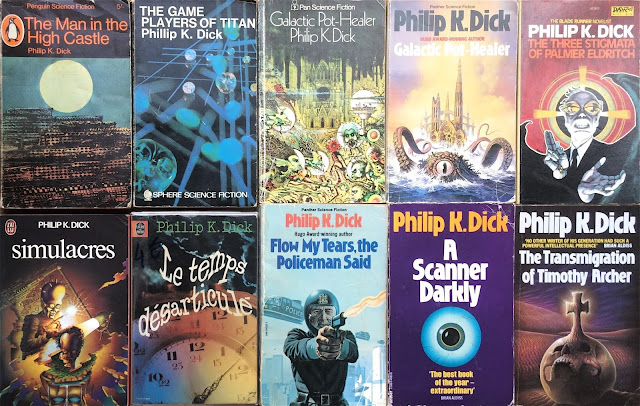

The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, by Hawthorne Abendsen (Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle),

to K/L. Callan’s Marx, Christ and Satan United In Struggle (Stewart Home’s Red London), to

The Benefit Of Christ Crucified (Luther Blissett’s Q), to

The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy (Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy), to the endless quotations of Stewpot Hauser and Out To Lunch (Ben Watson’s Shitkicks and Doughballs), to the book within the book within the book within the book neo-pulp madness of Bobo the Monkey (Steven Well’s Tits Out Teenage Terror Totty). It’s all good baby and super meta.

Returning briefly to the issue of diversity, something that many well-known comics have struggled with in recent years. Though I am sure there are plenty of books telling stories other than those of hetro-normative, mostly white massive ab-ed and big boobed superheroes, it’s fair to say that many of the medium’s biggest sellers still have room for improvement. Clumsy attempts to make minor characters ‘come out’ still result in shitfits from keyboard warriors lamenting the fact that writers can’t make new, minor, LGBQT or POC heroes that they can ignore. Saga shouldn’t need to be lauded for starring loads of women (including breastfeeding mums), gay characters and every kind of alien-sexual preference you can think of, but it does feel uncommonly vibrant.

It’s not all politics, proxy wars, racism towards ‘horns and wings’ and baby McGuffins. Much of the story is about how hard it is to be a parent, the challenges of keeping relationships afloat and the pressures of daily life. There is much that is relatable despite the fantastical settings. Gun for hire The Will munches space-cereal and sulkingly blanks his ex’s calls. There are translation problems (the Horns speak some sort of Latinate, Esperanto language). Alana gets an acting gig on a space soap opera. Marko takes their toddler on play-dates. Unions struggle against employers. Mums – albeit ones with TV screens for faces – take their kids to the beach. People have baths. This is key to making the world of Saga appealing and enduring. It’s not all decapitations and saggy-testicled ogres, there’s hues of real life in all its humorous mundanity. And it does make you laugh. Liar Cat and the Royals with TV heads are the gifts that keep on giving and Staples’ artwork veers between heart-string tugging poetry and mischievous comedy.

Vaughn has made clear that much of the inspiration behind the narrative of the book came from the birth of his own child. Let’s leave the final word to him:

I realized that making comics and making babies were kind of the same thing and if I could combine the two, it would be less boring if I set it in a crazy sci-fi fantasy universe and not just have anecdotes about diaper bags … I didn’t want to tell a Star Wars adventure with these noble heroes fighting an empire. These are people on the outskirts of the story who want out of this never-ending galactic war … I’m part of the generation that all we do is complain about the prequels and how they let us down … And if every one of us who complained about how the prequels didn’t live up to our expectations would just make our own sci-fi fantasy, then it would be a much better use of our time.