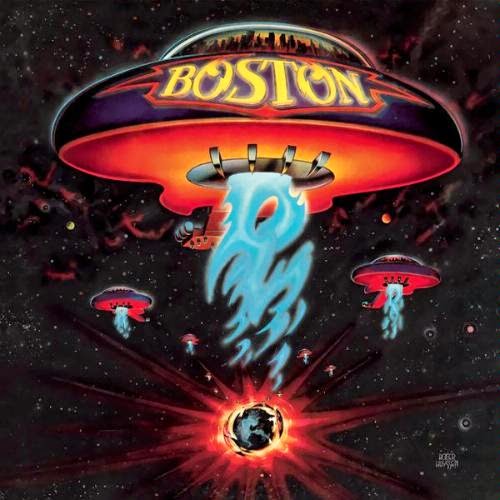

The Kepler Space Telescope first picked up the star in 2009 and the swirling mass was initially thought to be bad data movement. However, over time, it became clearer that a cluster of objects was orbiting KIC 8462852, because of the light pattern emitted by it. In fact, further investigation of the star was partly thanks to several citizen scientists on the Planet Hunters project, who flagged up its strange and interesting formation. Boyajian and her colleagues published a paper on KIC 8462852 that models natural scenarios to try and explain this, for example a giant ring system or fragments due to the break-up of a large comet. Yet other hypotheses remain, one being that it is a set of alien megastructures for harvesting light from the star. Of course, such theories are part of the reason KIC 8462852 attracted so much press attention. Nevertheless, significant funding goes into maintaining the search for alien life. The Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute has focused on looking for potential intelligent signals for over half a century, and astronomer Jason Wright was quoted as saying that KIC 8462852 is ‘the best SETI target I've ever seen or heard of’. Wright is publishing a paper with an alternative interpretation of the star’s light pattern, which also considers how to distinguish possible artificial megastructures from other anomalous objects. The paper is available to view here.

|

| KIC 8462852 |

The news of KIC 8462852 coincided with a similarly exciting October event I attended, Andrew Rushby’s talk, ‘Exoplanets and the Apocalypse’, as part of the Café Scientifique public lecture series. Rushby, who is set to take up a post at NASA in 2016, gave an overview of his research on exoplanets, which are planets that orbit other stars beyond our solar system. His research investigated Earth-like (or habitable) exoplanets and their lifespans, in order to model what might happen when the world ends (about 22 billion years from now). One of the most interesting asides to the talk was about the possibility that some of these Earth-like planets might support life as we know it, i.e. carbon-based life. Rushby suggested that the development of an instrument sensitive enough to reliably analyse planets’ atmospheres could lead to the detection of chemicals such as cfcs. This would constitute evidence of artificially generated gases and hence intelligent, industrialised life. Personally, I find the idea of aliens burning non-renewable energy sources a bit disheartening; on the other hand, the thought of a giant light harvester perhaps offers a glimmer of extra-terrestrial hope.